Universal Basic Nutrient Income, in conversation with an unusual duo

A conversation between

Aleksander Nowak, Alexandra Hansten and Nathalia Del Moral Fleury

“Food is our common ground, a universal experience.”

By James Beard

“How do you go from studying architecture to investigating the Danish pig industry?” I asked. Aleks leaned back in his chair and smiled like he’d been waiting for this question. “I get that one a lot.”

Aleksander Nowak—Aleks, to everyone who knows him—is officially an architect, but unofficially he’s a lot of other things too: coder, researcher, systems thinker, strategist. Like most people at Dm, he doesn’t fit neatly into one category.

Alexandra Hansten (also known as Alex)—the other half of this unusual duo—laughed when I asked her the same question. “I’m trained as an architect too. I graduated just as the market got really shaky, so I widened my scope.” She had started with some graphic work for Dm but quickly got pulled into a full-time role. “I didn’t have a background in food systems,” she admitted. “Except for the obvious: I eat.” But the more she got involved, the more it pulled her in. “It felt real, urgent, something you just can’t not care about.”

Aleks mentions that the project started with him helping with data visualisation and mapping for a book publication about the spatial impact of societal, economic and political changes in Denmark from the haydays of its welfare state in the 70s up until today – everything from centralization of hospitals, schools, and overall decaying periphery in favour of the bigger cities. This led me to playing with a lot of data – and Denmark is a paradise for data nerds! – they usually have open data on everything! So I started to also make maps on the side of this project and ended up realizing that one of the main invisible “infrastructure” of Denmark are the pigs.

I raised an eyebrow. “The pigs?”

“Yes,” he said. “Denmark’s covered in monocrops. Over 60% of our land is used for agriculture. And of that, around 80% is for pig feed. There’s 28 million living in Denmark out of which half million are slaughtered every year. That’s almost 5 pigs for every person in the country.”

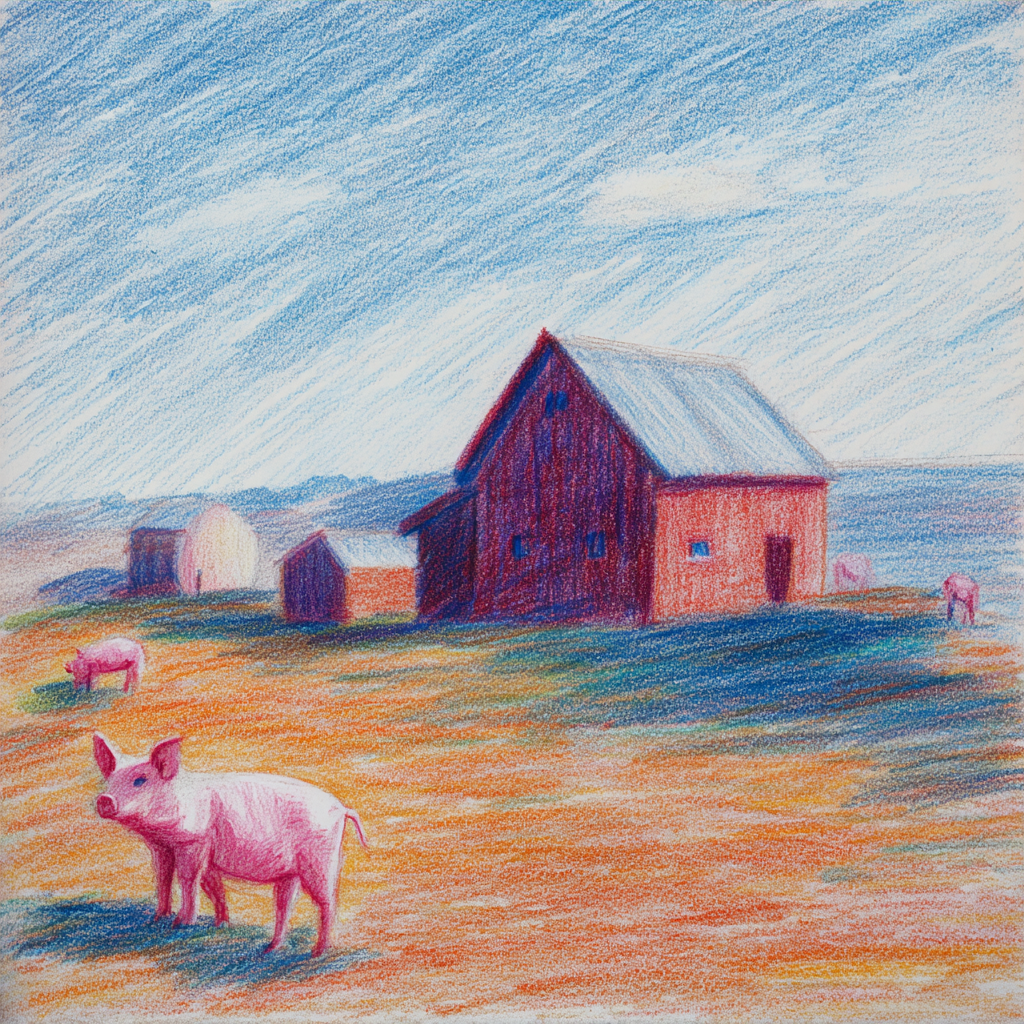

Aleks explained how driving through Denmark—or any country, really—you start noticing it. Endless fields, often presented as a pristine, comforting countryside, like the background of a children’s book: cows grazing, golden wheat waving in the wind, clean skies. But the reality is different. These fields are a product of optimization for extraction. They’re often draining the soil, saturating the land with pesticides, and growing food not for humans—but first for pigs. “And once I saw it,” Aleks said, “I couldn’t unsee it. The countryside and food systems became a bit of an obsession.”

Once you become aware of it, you realize how much land is organized for production. And also how much of that produce goes directly into feeding our livestock.

What’s the issue?

“This isn’t just about pigs, which, just to clarify, I do not want to reduce merely to infrastructure – they are feeling, intelligent living beings just like us” Aleks said. “It’s about how food is the foundation of everything, and we’re treating it as if it’s invisible or a given.” In the meantime, we are careening toward a 3-degree Celsius world, and our food systems are both a driver and a casualty of this trajectory. Our current Western diets, built on meat, processed calories, and long-distance supply chains, are contributing to emissions, deforestation, and social fragility. Agriculture subsidies promote industrial farming and monocultures. Pesticides continue to poison our waters. And all the while, highly processed food fuels a health crisis—rising obesity, soaring diabetes, and an explosion in demand for drugs like Ozempic.

Alex jumped in: “Exactly. It’s also about how we price food, and it’s a reflection of what we value. We purchase food based on its weight – not based on its nutritional value. Isn’t that wild if you think about it?”

As the duo progresses, they keep coming back to the same tensions. Alex shared: “Producers need clear market signals from consumers. Consumers need better options and clear guidelines. But there’s this in-between—funding systems, procurement, policy—that doesn’t allow the relationship to shift. That’s why we started imagining something more radical.”

Alex added. “As part of the work with the Innovation platform we made this diagram, showing the planetary impact of the current Swedish diet versus the one of the Eat-Lancet Planetary Health diet. The gap between the two is clear, but the road there, less so… It hit me that this shift isn’t just about making consumers eat better or shifting what products we produce, it’s a systemic shift where “both sides” of the value chain depend on each other as well as the structures in between. . .”

Food is not just a personal health issue—it’s geopolitical. As climate extremes escalate, food prices will rise. Aleks warns, “When food systems collapse, civil order often follows.” Food is about national security, it is about preserving safety.

“Safety?” I asked him what he meant by that. “You might have food in northern Europe,” he said. “But it won’t matter if the rest of the world collapses. Social systems are interconnected. Hunger somewhere else becomes instability everywhere. That’s why strategies for resilience know no administrative borders”

And what are you doing about this massive problem? I wondered out loud. One thing they did to make people feel the stakes, and not just understand them, was to design an experiential dinner. It is a simulation more than a meal, to translate many complex issues in a lived experience.

“It is a bit of an experiment as to how we can use immersive experiences to start difficult conversations” Alex said. The dinner is part of a Vinnova funded speculative design project under the name “Universal Basic Nutrient Income”, where we have explored ideas for seeing food as part of our healthcare, welfare infrastructures, and as new models for citizen participation in local food production chains to increase local resilience and preparedness. These small prototypes showed glimpses into potential alternative futures where new ways of organising helps mitigate the risks of a potential food system breakdown. For example, during this project we allowed a group of people to test how it would be to exchange a day of regular office work to working at a farm.

Coming back to the dinner, Aleks and Alex designed the experience from start to finish.

The dining room was set up like a stage. One long table. Warm lighting bathed one side in golds and greens, with plants weaving between dishes and chairs. The middle of the table was dimmer, neutral. The other side was flooded in sterile neon, all sharp whites and blues.

Alex shared, “this dinner was one of the most impactful things I’ve worked on. People entered buzzing with energy. But as soon as they got their roles—future personas, emotional states, what they could eat—the room changed.”

Each guest received a card—a roleplay scenario describing who they were in this speculative future: their name, their age, their job, their income, their emotional state. Guests looked across the table uneasily when they started to read each others card.

Then, the food was served.

The lush side received a vibrant salad—crunchy greens, grains, edible flowers. The middle section, representing the “business as usual” 2-degree scenario, got dry bread with margarine. The final group, the 4-degree scenario, was served a small shot of nut oil. That was it. “Nut trees are resilient,” Aleks said with a shrug.

“What surprised us,” Alex said, “was that the ‘business as usual’ group were the most affected by the experience. Not the worst-case group. The ones who got dry bread and margarine. They saw the trap we’re stuck in—and it made them ask: Why are we even trying to preserve this?”

The silence was thick. Laughter died quickly. Someone whispered, “I feel like I’m in prison.”

Even though they knew it wasn’t real—even though they’d go home and eat what they wanted—something deep struck them. “We use food to socialize, to feel pleasure, to mark time,” Aleks said. “When you take that away, something in your body reacts. They felt discomfort. The conversations became tense. They felt excluded. And that’s what we wanted them to feel to understand the plausible future if we do not act now”.

Alex nodded. “You feel it in your body. That’s why food is so powerful. It’s not abstract. It’s embodied. People got emotional, even anxious. And yet we were just playing pretend.”

What is the transformation?

Transformation is happening—but slowly. Aleks describes a two-pronged approach: changing how people feel about food (the demand side), and changing the structures that produce food (the supply and governance side).

The dinner experience is part of the former. “People need to feel it in their bones,” he said. “Rational arguments don’t move systems. Emotions do.”

Beyond emotional activation, Aleks and Alex’s team works at a structural level. The Universal Basic Nutrient Income, is a radical rethinking of how society ensures every person has access to nutritious food within planetary boundaries. Inspired by Mariana Mazzucato’s mission-driven policy models, they pose this question: What incentive structures do we need to build so that 9 out of 10 meals in Sweden were served within ecological limits in 15 years time?

“We’re figuring it out as we go,” Alex explained. “In Sweden, we have come a long way in terms of improving the sustainability of our food systems, but we still have a long way to go. We’re trying to build the enabling conditions for systemic change—not just the solution itself, but everything that lets a solution take root.” The core team is small—just the two of them, mostly—but they’re bringing in expertise from the wider DM team. In the platform work, they see themselves as neutral ground for aligning actors around a common mission, a kind of relational infrastructure. “We’re not ourselves primary producers or policymakers— our role is to be catalysts for the change we wish to see” Alex said.

This is not just a utopian vision. They bring together stakeholders from across the food system—farmers, policy makers, grocery retailers, NGOs—and guide them through future scenarios, systems mapping, and innovation design. “We’re not here to impose solutions,” Aleks said. “We help actors find their own leverage points and build coalitions around them.”

But it’s difficult. The institutions, their capacities and capabilities, aren’t ready. The decision making systems are siloed. The funding is fragmented. And there’s a deep inertia. Institutions lack vision on the food systems beyond what we already have. And even if we co-create these visions then we come back to the implementation gaps. The question is – how much of the shifting context will actually superimpose the new version of the food system on us first?

What is changing with this project?

The most powerful shifts are qualitative at this stage, not quantitative. Individuals and institutions are beginning to see food differently—not just as a commodity, but as a foundation of health, culture, and planetary stability. The dinner and UBNI concept has gained a lot of attention, Aleks shared they are building a toolbox so that experiment can be replicated in other places. They’ve received requests of interest from different organizations and individuals to create dinners like this across the globe. The visceral experience is working and inspiring others to become agents of change. And perhaps most importantly, people are talking. The vision isn’t just to reduce emissions. It’s to rebuild food as a source of joy, connection, and regeneration.

BEYOND EXTRACTION:

From industrial food production, that creates harmful externalities that extract life from soil, air, water, and other resources; to regenerative production, that is generative for all life forms involved directly and indirectly in the production of the food, including its consumption.

The traditional current model: Land is used for maximum yield—typically monocrops to feed livestock—driven by short-term profit and subsidies. The new regenerative model: Land is a living system. Agriculture, transportation and transformation of food supports biodiversity, soil health, climate resilience, and human thriving.

Example: Aleks’ critique of Denmark’s pig-feed monocultures challenges this model directly. Their vision includes bioregional food networks and diversified farming systems that return vitality to the land. Options in which city people can dedicate one day a week working the land and getting food in exchange.

BEYOND GOVERNANCE:

From centralized control to collective stewardship.

The traditional model is based on centralized institutions, controlling food production through subsidies and regulations and a siloed budget. The new narrative: Governance becomes a distributed process of shared visioning and experimentation, where complexity is mapped into the decision-making process. Health and diet planning are intertwined, and there should be open conversation between these two governing areas.

Example: In Sweden, cross-sector actors were brought together to co-design a mission-driven food policy. They moved from isolated roles to shared responsibility.

BEYOND PROPERTY:

From land ownership to land care.

The traditional model is based on private land ownership with extraction rights. The new narrative: Stewardship-based models where land is managed for long-term community and ecological benefit.

Example: Although not directly in the food system project, Aleks referenced Re-Land and Terre Noire in Canada as models of community-centered land governance that could inspire future iterations.

BEYOND PRIVATE CONTRACTS:

From single point transaction to mutual commitments.

Traditional Model: Trade agreements and procurement policies focused on price and efficiency. New Narrative: Long-term partnerships oriented around shared outcomes like nutrition, climate, and equity.

Example: The Universal Basic Nutrient Income imagines a future where contracts are designed to deliver health and ecological value, not just volume.

BEYOND LABOUR:

From exploitation to revaluing work with the land

Traditional Model: Agricultural labor as low-status, underpaid, and aging. New Narrative: Revaluing farming as vital, dignified, and creative. Rebalancing urban-rural workforces.

Example: Aleks and Alex envision networks of bioregional farms, supported by local currencies and new career paths, where youth are drawn back to the land not through nostalgia—but purpose. A four-day week allows for a fifth day, that could be repurposed to feed ourselves.